The Complex Intersection of Patriarchy and Caste in Indian Society

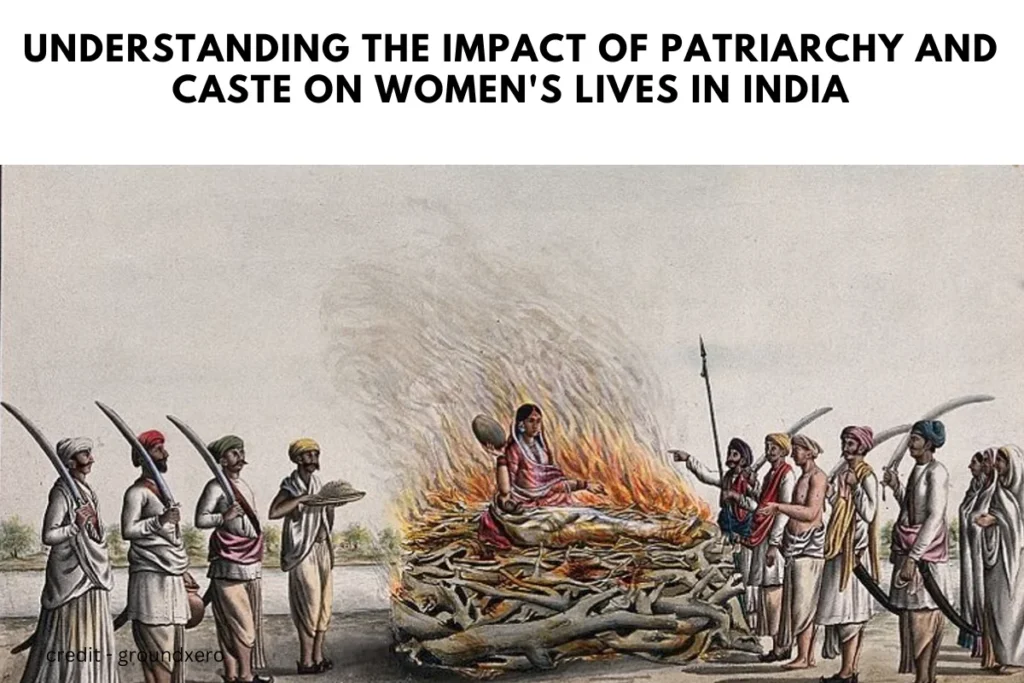

Indian society has long been plagued by patriarchal systems like purdah pratha, child marriage, and the view that women’s purity symbolizes status. While some of these issues have been addressed through legal reforms or social efforts like widow remarriage and the abolition of sati and jouhar, much more needs to be done to foster a truly inclusive environment for women.

Female labor force participation (FLFP) in India stands at just 35.6%, including employment from schemes like MGNREGA. For India to become a $5 trillion economy, it is essential to address the societal structures holding women back. To find solutions, we must first understand how these structures operate and how they differ across various castes.

During colonial times, practices like sati were widespread among Rajasthan Rajputs and Brahmins. These customs placed immense pressure on women to prove their purity, especially among the upper castes. This burden, combined with high wedding expenses, contributed to societal issues like female infanticide and dowry demands. The British were shocked by the extravagant wedding expenses, which were seen as a display of wealth and power by the upper castes.

Data from the Ministry of Statistics suggests that rising per capita income often results in a decline in FLFP, as men with stable incomes prefer their wives not to work outside the home. In essence, women remain victims of both casteism and patriarchy, regardless of their caste.

Scholars like Periyar and Ambedkar have argued that women, like Dalits, suffer under these oppressive systems. However, the intensity of their suffering varies across caste lines. Upper-caste women often face more orthodox constraints than lower-caste women. In lower-caste, poorer families, financial struggles often lead to less rigid observance of traditions like purdah.

For instance, in impoverished households, 12 to 14 family members may share a single room, making it nearly impossible for women to observe purdah around male family members. In contrast, upper-caste families with more resources can afford separate spaces, allowing women to follow these customs for longer periods. Similarly, in rural areas, women from lower castes often bathe at communal hand pumps or lakes, while upper-caste women are expected to bathe in isolation, typically before sunrise, to avoid being seen by men.

These examples highlight that upper-caste women, bound by stricter patriarchal norms, often face more significant oppression than their lower-caste counterparts. However, women from poorer, lower-caste families may face other challenges, such as financial pressures, which often lead to more progressive practices like allowing women to work.

In conclusion, while women across all castes face the burdens of patriarchy, the experiences of upper-caste women are often shaped by more rigid orthodoxy. The claim that all women suffer like Dalits needs deeper examination, and society must make concerted efforts to bring women into the mainstream.

for more updates follow ANN MEDIA on facebook , X , Instagram and Linkedin